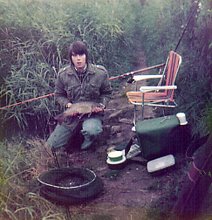

I had recently started my

trout fishing life in Kent, with a friend who patiently taught me how to cast

and had the inspired notion of ensuring that I caught a fish by teaching me in

a place where it was easy to do so – a fish farm. My first Rainbow weighed in

at around two pounds, fought like a locomotive and – because you paid for each fish

you caught – cost me about eight quid!

But of course I was hooked too. There is something so

simplistic, so condensed about turning up at a water with a rod, a small bag and a net. No

bait, no seat, no rigs or weighty bombs to cast at the horizon – it seemed so

pure, so refined and so light! It was apparent that it would be easy to become

snobbish about the virtue of this inherent simplicity. And of course you could

always leave the bag behind too because fly fishing is the only time in life that grown men could and should wear a waistcoat. I have seen some older gentlemen

sporting “gilets” while boarding aircraft or strolling along the promenade at Brighton –sometimes it’s almost a uniform in the checkout

at Heathrow - but it really shouldn’t be allowed. I blame the wives of these

safari gilet wearing warriors for permitting them to leave the house in such

attire – waistcoats are for, and only for,

fly fishermen.

|

| Fish Farm Trout |

|

| Waistcoated |

I went on to fish a local

reservoir; a vast water with depths of up to 70 or 80 feet but where the

majority of the trout are caught near the surface for most of the year, only

becoming unreachably elusive during the extreme heat or the severe cold. I

loved the splashy rise, the gentle sip or the “roll over” as the flies were

taken and, for a while became adept on the bank and in the boat – by adept I

mean that I occasionally caught a few of these ‘wilder’ fish and my casting

improved. I enjoyed the solitude of these larger waters, though of course, the

fish were still stocked; on the borders of Kent

and Sussex

I came to appreciate the art

of tying my own flies, always preferring to use natural materials, or at least

natural looking flies whenever

possible. Much of my writing about trout fishing traduces the “lure” – that

flashy imitation of nothing earthly - that angers a fish into snapping at your

“fly”, rather than taking one that it has been fooled into believing was a

nymph or midge lava or even a fry. Yet although I have used lures, especially

on the ‘dog’ days, when fish are reticent, deep or sleepy, I’m not very adept

at fishing them and feel less satisfaction catching with them – I am very

definitely a nymph man at heart.

But in 1990 I ‘discovered’ Scotland

Naturally, the love of

fishing and the love of Scotland

As far as Scottish fishing is

concerned, there are so many famous places and rivers. The sea at Malaig and

Oban, the lochs of Leven, Lomond, Ness and Ken, the rivers Tweed, Spey, Dee,

Tay and Don and a myriad of smaller rivers, burns, lochs and lochans – even one

lake. There are towns whose names are synonymous with the sport, Dunkeld,

Beauly, Kelso and Thurso and the entire country is veined with meandering

watercourses and potholed with glacial lochs of vastly differing sizes – it is

a veritable dream country for a fisherman.

It was in a marginally famous

river that I caught my first Scottish and truly wild, brown Trout – the

Blackwater.

It’s namesake in Ireland –

the Munster Blackwater - is probably more famous, starting in Kerry and flowing

out through Youghal harbour in County Cork with some magical salmon and trout

fishing beats in between. I have fished that river too, now. As we walked down

towards the falls of Rogie from the car park towards the Scottish Blackwater

near Contin, salmon were showing everywhere, splashing in pools as they fought

their way up-river in the inevitable battle against contour and elements to

spawn. I was persuaded by my girlfriend to fetch my gear from the car and have

a go, so I did, to some extremely disgruntled looks from the Salmon Angler

opposite. I tied a small red tag stick fly to a four pound point fishing as I

would in a fish farm stew pond back home – not knowing any better - and cast it

into the pool.

It felt like a momentous occasion that first

cast, almost ‘heavy’ yet I felt lightheaded; my hand tremulous, my breathing fast

and light. I didn’t want to catch a salmon – Heaven knows I wasn’t ready for

that yet – I just wanted to ‘fish’ and I wanted to hold a real, proper wild,

brown trout in my hand and just look.

It was perhaps three or four

casts later that I caught my first ever Scottish Brown Trout – a tiny, dark

peaty fish of maybe six inches or so. I was like a small child on his first

ever minnow fishing trip, amazed and filled with awe at the cascade of colours

on these predominantly green fish, but with so many swirls, whorls and blotches.

I counted several other colours and, surprisingly, not much actual brown. Only

six inches, but that first trout from Scotland

It was a wonderful moment in

time; the very slight pull on the line - sometimes like a breath of gossamer,

or as if a slight breeze had caught the material of the fly - would cause my

hand to twitch the rod a fraction of a second later, yet often that fraction,

that slight hesitation between sensation and brain impulse was eons too long in

trout time, the fish had already realised its mistake and spat out the coarse

imitation in disgust. Yet I had fooled it for an instant. I had duped the trout

into thinking that my size 16 twinkle midge was a real insect, a genuine item

of food. It didn’t matter that all the fish were small, what mattered was the

moment, the whole short episode of time, the period in which everything around

me tunnelled in on those few fish, that short, magic spell of catching ones

first truly wild trout.

By this time the surly salmon

angler had moved downstream and I was inexorably drawn back to the ‘real’ world

by a loud splashing and sudden movement on the opposite bank. I watched

entranced as he played and then lost a large tail-walking salmon. The fish was

there one second and gone the next, the line sagging towards the water like a broken

washing line as the water of the pool resumed its slow, washing-machine tumble.

I would have been completely distraught, raving and stamping around, throwing

my rod in the bushes and chewing through the nearest tree trunk, but he just stood

looking blankly at the water, still for a moment, then seemed to give an inward

shrug before retying his cast. No doubt his fate was different to mine; he has

probably caught many salmon each season and one lost fish is just another

episode in his ordinary, daily life.

I felt that it was time to

retreat. The tranquillity of the pool had been transformed into an angry,

brooding entity, the benignity had gone, the still quietude banished. The dark,

rocky shelf surrounding the pool was now a forbidding presence, a malevolent

gaoler rather than a welcoming gatekeeper.

As I climbed the hill back to

the car park it occurred to me that I had been blessed with some nice fish as a

gift, if you like, from the river, and this feeling has been prevalent from

time to time over the years. I have learned to react to the changing character

of rivers, lochs and lakes, when I am astute enough to feel these imperceptible

nuances of character shift and to accept the gifts when given with thanks.

Sounds daft? Well ok, I can accept that in the here and now, but I will still watch

for those mood changes and I will welcome them as gifts or warnings as

appropriate.